‘The Jungle Book’ Review: A Visually Stunning Adventure (But Not For Small Children)

Kids grow up so fast these days. They have to if they’re going to watch the movies Hollywood makes for them.

Just weeks after the release of a nearly R-rated movie about Batman and Superman comes a new version of The Jungle Book with eerily realistic animals biting and clawing the hell out of each other. The movie is so frightening that some TV ads for the PG-rated adventure feature an unusual disclaimer warning potential audiences about “scenes that may be intense for young viewers.” If Mowgli were a paying customer, in other words, he wouldn’t be old enough to watch his own movie.

To a certain extent, that is a compliment. Director Jon Favreau and the miracle workers of Weta Digital have teamed to create one of the most impressive CGI worlds to date. The young boy who plays Mowgli, Neel Sethi, is the only human onscreen for nearly the entire runtime; almost everything else around him, from the trees to the rivers to the fires to the animals that share his story, was created inside a computer. The Jungle Book’s illusion might be too convincing for its own good — there’s a reason that TV spot has that disclaimer — but it’s so persuasive that the notion of these photorealistic beasts carrying on conversations feels plausible from the very first scene.

That conceit comes from the original Jungle Book stories of Rudyard Kipling and the 1967 animated musical from Walt Disney Pictures, where Mowgli traveled through an Indian jungle with sly bear Baloo and wise panther Bagheera. The new film, written by Justin Marks, follows the cartoon’s basic outline with more action and fewer moments of levity; years from now, scholars may find it instructive to place these two Disney Jungle Books side by side to consider shifting tastes and Hollywood priorities through the decades.

Only two of the ’67 Jungle Book’s songs remain: the iconic “Bare Necessities” and the catchy “I Wanna Be Like You.” Both are wildly out of place amidst the chases, brawls, and thundering animal stampedes of 2016; they seem to belong to a different movie — that being the 1967 Jungle Book, whose pace and tone were dictated by the laconic Baloo (the new movie owes more to the constantly-in-motion Mowgli). The songs’ presence in the new Jungle Book feels less motivated by the needs of the story than a studio that wants to keep old school fans happy (and possibly sell them a new version of a perennially popular soundtrack). The sudden shifts from goofy melodies to aggressive combat are jarring and off-putting.

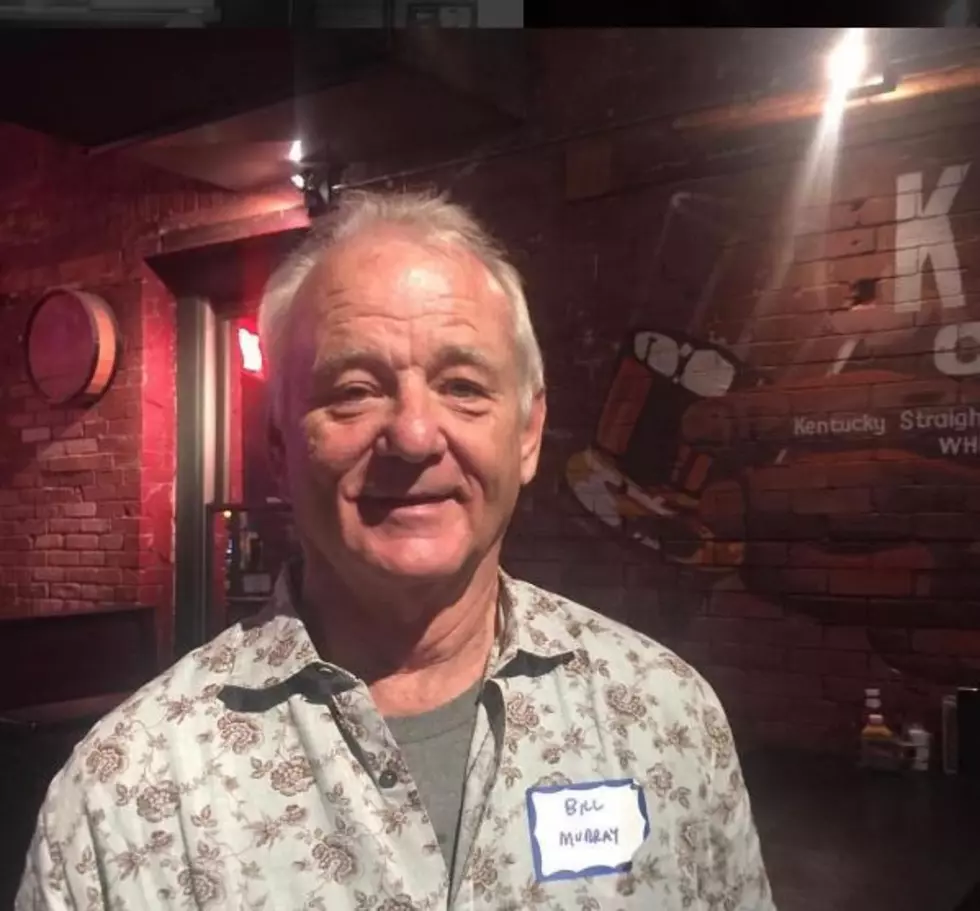

On the plus side, the big-name voice talents are all perfectly cast. It’s hard to imagine a better replacement for Phil Harris as Baloo than Bill Murray; a whimsical, carefree bear who loves to sing badly and dispense folksy advice to young people is basically the Ghostbusters star’s spirit animal. Idris Elba is equally memorable (and far more intimidating) as Shere Khan, the ferocious tiger who sets the plot in motion by demanding Mowgli’s wolfpack (including his adoptive mother Raksha, voiced by Lupita Nyong’o) hand over their “man-cub” for his immediate ingestion. Mowgli leaves the pack with Bagheera (a regal Ben Kingsley), but the two are quickly separated, and the boy eventually wanders into the ever-tightening embrace of the hypnotic snake Kaa (Scarlett Johnasson) and then the angry gigantopithecus King Louie (Christopher Walken).

Louie might be this Jungle Book’s most impressive technical achievement and its most confusing character. A giant brute of an ape, he’s introduced in a clear homage to Marlon Brando’s similar performance in Apocalypse Now, mumbling in the shadows of a decaying temple. His facial expressions, the faint resemblance to the real Walken, the shift and sway of his matted fur; it’s all incredible. Then he demands Mowgli hand over the secret to mankind’s “red flower” (aka fire), which will make him the lord of the jungle. When Mowgli refuses, Louie serenades him; after a failed rescue attempt from Baloo, he hunts Mowgli through temple in spectacular and kind of terrifying fashion. So he’s just your run-of-the-mill deranged, fun-loving, monstrous ape with a song in his heart. He’s all of The Jungle Book’s strengths (gorgeous imagery, dynamic action) and weaknesses (Is this a gleeful kids’ entertainment or a propulsive blockbuster for adults?) rolled into one.

Sethi looks exactly like the cartoon Mowgli (and we finally learn, in classic everything-in-modern-movies-must-include-an-origin-story fashion, where he got his red shorts) but his performance sometimes gets overwhelmed by the technological splendor around him. (It’s hard to blame him; it can’t be easy for a child actor to play an entire movie to green screens and dudes covered in tennis balls.) Favreau’s Jungle Book is at its best in moments of visual splendor; when his camera pulls back to admire the sweep of the CGI foliage or yet another dazzling computer creation wanders into frame. Those images have a clarity that the rest of the movie often lacks.

More From 99.9 The Point